Facing Calamities - A fieldstory from Western India

My fieldwork experience

Natasha dressed in traditional bridal attire

Natasha Maru

'Did you have fun?' asked my brother when I got back from fieldwork in September 2015. The light-heartedness of the question evoked strong feelings in me because fieldwork for me had been quite an intense, serious affair. And while it had been confusing, lonely, stressful, anxious, earnest, creative, cathartic, fulfilling and enormously empowering, what it had not been was 'fun' in the way he thought it.

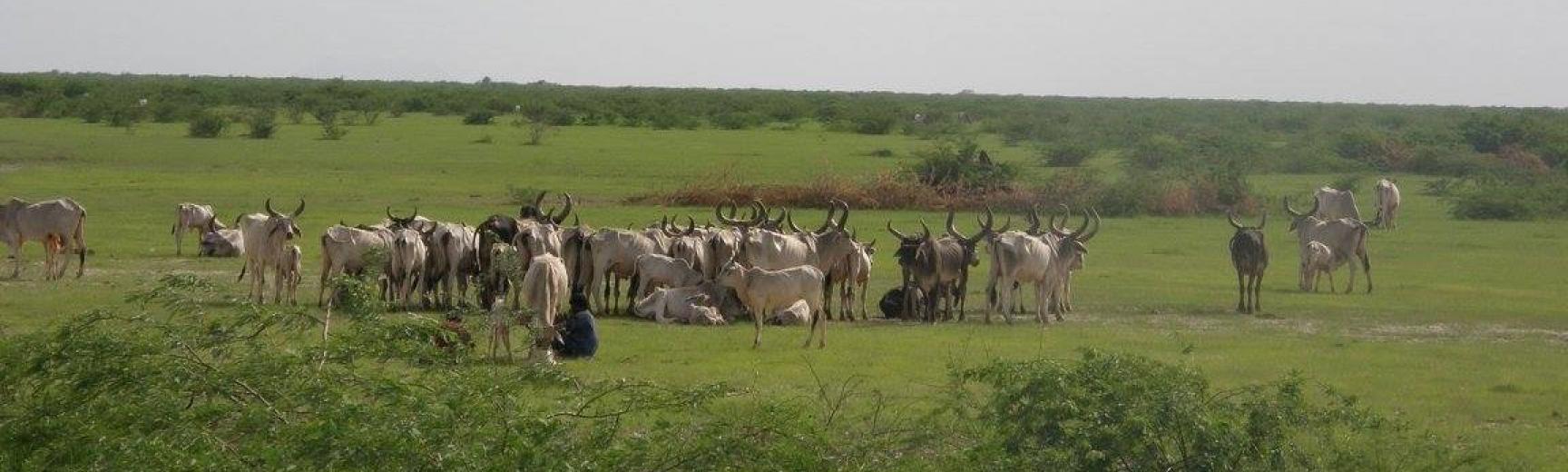

A student of the MPhil in Development Studies, I spent two months in the summer of 2015 conducting interviews with a community of semi-nomadic pastoralists that occupy the Banni region in the Western border district of Kachchh, India. Referred to as Asia's largest grassland, this drought-prone semi-arid region becomes an island of green when it receives rainfall, while in non-rainfall years it blends with the desert that surrounds it. My thesis aimed to explore state-society relationships through an ethnographic study of the local bureaucracy in the region in light of its changing political economy, privileging industry over pastoralism. Despite having done my reading on governance in the region, I found that the bureaucracy on the ground was not something I would be able to study given my time and access constraints. I eventually ended up writing about resource use, rights to resources, and the multifaceted state-society relationship in relation to these.

Taking care of your emotional health during fieldwork is very important, but, especially in the absence of trauma, is often unplanned for by students and not fully recognised by faculty. Therefore, in writing this piece, I aim to emphasize the emotional challenges I faced while facing exceptional, and not-so-exceptional, circumstances in the field.

I specifically mention the duration of my fieldwork to draw attention to the kind of issues students on short-term fieldwork face, challenges that remain undermined because of the limited scope of the projects undertaken by Masters Students. Conducting fieldwork for a limited time, I felt stupendously under pressure to perform, to take quick decisions and to work within the constraints of limited research funding.

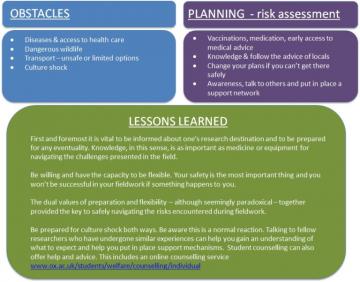

I was at least glad about having my logistics in order, but this, too, was short-lived, as my fieldsite experienced the greatest rainfall it had had in 30 years beginning the day after I arrived. The sandy soil of the region prevented seepage, causing massive floods, with the pastoralists having to leave their villages and relocate in temporary shelters made of bamboo and tarpaulin sheets, and the local government needing to break the main roads to let the floodwaters out. The rainfall led to an 11 day blackout, zero cellphone reception, transport disruptions, and food and water shortages in the region. The community I was working with restricted the movement of their women out of their hamlets for socio-religious reasons, and my family, more than me, were a bit unnerved at the thought of my safety being entrusted to unknown men in these exceptional circumstances. Questions of what to study and where to study bogged me down, and the thought of being away from the comfort of home and family, during what was meant to be my summer vacation, only added to the helplessness and loneliness I felt. Each passing day was precious; I had no connections or knowledge to readily switch fieldsites in light of the flood.

Faced with such circumstances, I decided to stick to my initial research plan, rather than changing it, as I felt most comfortable with the idea of researching a case I had made myself familiar with. This meant that I lost a couple of weeks of interviewing but I used that time to become better acquainted with the region, reading and having as many conversations as I could to refine a new research plan. I gave myself a two week limit at the end of which I conducted a reconnaissance trip to my targeted villages. What would have otherwise been a 40 minute bike ride, now took 4 hours of travel because of the lack of access. Additionally my respondents said they would be moving base every fortnight as the water receded. Daily commute as planned initially would be impossible, and I would have to move from village to village, site to site, to have continuous access to my respondents. The challenge now was to find and negotiate with a field assistant who could travel with me to my fieldsite, help with logistics, as well as be a gateway to the locals, providing credibility by way of introduction; most importantly I needed to be able to trust my field assistant. Luckily, I was able to identify such an individual through my NGO contacts in the area.

Trusting my field assistant, Imran was the most important lesson I learnt. Recognizing that without his help I would not be able to achieve anything, respecting him for it, appreciating his insight as an advantage and building a strong relationship with him was extremely important; he understood what I was trying to do, what I expected, why it was important to me. Although Imran came highly recommended by my NGO contacts, he was still a stranger to me. It sounds simple, but trusting a stranger is difficult, especially in a social context where interaction between men and women is taboo on the one hand, and unequal in the man’s favour, on the other.

Before going to my fieldsite I had read literature about ethnic tensions and indeed noticed a negative social perception of the community; I was asked by multiple (Hindu) people in Bhuj (the district’s capital city) if I was scared/uncomfortable living with my respondents. Of course these negative social perceptions were proved false by my positive fieldwork experience.

On one occasion I was taken in for questioning by the Border Security Force who wondered what I was doing (as a non-local Hindu female) “roaming” about the border area with a young local Muslim man in a context where women are not allowed out of the home and men and women do not mingle in public. This was resolved as I had: my ID; a letter from my department approving research; a letter from local NGO (which was also submitted to the Intelligence Bureau for permission to live and research in the area); my visiting card; my father’s visiting card (being a young girl – this helped), as well as the contact of the local Superintendent of Police and an officer from another Border Security Force station (both of whom knew that I had research approval and was affiliated to the local NGO).

With Imran I moved to four different villages, most often sleeping in the rope cots with the women of the house, and for a week on a blanket (the household’s best blanket) on a stone floor in an out-house, eating the local foods. I found that being flexible, accepting my changing circumstances, and immersing myself within the community not only got the ball rolling for my fieldwork but also exponentially enhanced my understanding of the specific lifestyle of my respondents and of pastoralism as a livelihood. It helped me to really understand the issues I was trying to get at from their perspective, see why it was important, and thereby better frame my research. While the flood had left me distraught, the pastoralists were highly adapted to tumultuous environment conditions, and happy even without amenities and possessions. The intense experience also helped me in developing a working proficiency in the local language (one that I was familiar with prior to fieldwork), and it also helped my respondents trust me. In my readiness to embrace their lifestyle they saw a demonstration of sincerity and commitment to my research project. My second learning through fieldwork was to embrace change, be flexible with plans and arrangements, and to listen - really listen - to what my respondents had to say, on record as well as off.

My third important learning was to keep the big picture in mind. When faced with a calamity in the field, one can lose sight of the larger goals of the research project having to confront academic conundrums and emotional turmoil. It was important to remember that it wasn’t just the data I collected, but also what I did with it that mattered, and also keep in mind that all fieldwork was a rich learning experience. To constantly ask yourself what you're doing and why you're doing it can help to both cope with the situation as well as clarify the research process.

Though fieldwork was tough, at the end of the day I am proud of having committed myself to something, to feeling conflicted because it meant so much to me, and of emerging on the other side with new insights not only about my research case, but also about myself. No, fieldwork was not ‘fun,’ but it was many other things and so much more. As they say - there is always a light at the tunnel. In my case the light was green, as the grasses burst through the ground as the floodwaters receded in Banni.

* Individual travel health advice can be obtained from the University Travel Clinic Country specific health advice can be obtained from Fit For Travel

Emergency first aid training for fieldworkers is available from the University Safety Office

** The Student Counselling Service offer an on line service for students away from Oxford